Flames licked lightly the body of America's foremost expert on conservation, wildlife management, ecology, and wilderness.

Aldo Leopold died of a heart attack on April 21, 1948, near the renovated chicken coop and reclaimed Wisconsin farmland known to his family and friends as "the shack." He had been fighting a neighbor's trash fire gone out of control. It threatened the tens of thousands of pines and hardwoods he and his family had planted. He set down the water pump he had carried to fight the fire, and lay down to rest his head on a clump of grass.

The morning of his death, Leopold counted a flight of 871 geese flying into the nearby Wisconsin River of Sauk County. The geese were attracted by the cover and food provided by the Wisconsin woods Leopold had worked so hard to restore. Just the day before, he, with his wife Estella and his youngest daughter, Estella Jr., added 100 more pines to the stand of some thirty thousand trees and shrubs planted over 11 years at the shack.

At 61 years old, Aldo Leopold was the elder statesman of the American conservation movement. Two months earlier, he'd been appointed to the United Nations Economic and Social Council's International Scientific Conference on the Conservation and Utilization of Resources.

In February of 1948, he had begun teaching Wildlife Ecology 118 at the University of Wisconsin in Madison for the fifteenth year. The class had a record 97 students. "The Professor" began the course by saying, "To formulate hypotheses about wildlife, and to test them for conformity to observed facts, is wildlife ecology. A person is an ecologist if he is skillful in seeing facts, ingenious in formulating hypotheses, and ruthless in discarding them when they don't fit." Aldo Leopold was an ecologist.

One month earlier he had attended, as Commissioner, a meeting of the Wisconsin Conservation Commission and voted to defeat a move to approve hydroelectric dams on the Menominee, Chippewa, and Wisconsin Rivers. He stated for the record, "The building of a power dam is an act of violence on nature and it is up to somebody to prove a dam will make the river more valuable than it is without it."

The previous year, he was elected honorary vice president of the American Forestry Association, and president of the Ecological Society of America.

He offered a new graduate-level course in Fall of 1946, called Advanced Game Management 179 "to develop the student's ability to think critically." This, after he had worked unsuccessfully all summer to convince the Conservation Commission to allow another any-deer hunting season to reduce the herd, saying "I want my exact words in the record. The same public which now insists that we postpone our [deer] reduction program will ask us, after the starvation is over, why we did not foresee it."

In April of 1945, the Leopold family planted 935 pines and tamaracks at the shack. They were heartened to find that natural reproduction had increased the plantings of aspens, birches, cherries, red osier dogwoods, willows, and other shrubs planted over the previous ten years. Leopold remarked, "The trees are getting awkward to measure."

Earlier in the year, he stood up as Conservation Commissioner to the public outcry for reenacting the predator bounty saying "I shall fight for again discontinuing the bounty whenever extermination again threatens. We have no right to exterminate any species of wildlife. I stand on this as a fundamental principle."

November 25, 1944 was opening day of the deer season in Wisconsin but, though he and his family were at the shack, Leopold did not hunt that year for the first time in many years. The previous spring and summer had been spent calling for a second any-deer hunt in order to further reduce the herd to Wisconsin's estimated carrying capacity of 200,000 deer. The Wisconsin Conservation Congress, a representative body of hunters from around the state, voted for a buck-only season and the State Conservation Department concurred. The Conservation Commission, on which Leopold served, would not vote against the wishes of both the hunters and the State's game professionals, no matter how pursuasive the arguments of Professor Leopold.

Spring planting that year included 475 tamarack, 500 red pines, and 1000 white pines. Leopold heard a loon at the shack for the first time.

The previous deer season had come to be known as the "crime of '43." An antlerless season had resulted in 128,000 deer taken — three times more than any previous year. The kill was unevenly distributed, however, so some areas were hardly touched, especially the northern counties deep in snow, while other counties reduced the herd by as much as 90 percent, when a reduction of 50 percent would have sufficed to improve the herd. Leopold, himself, suffered a tremendous loss when one of his favorite hunting dogs was injured by a wounded deer. Gus had to be put down by the hunter, who would never hunt deer again.

He had been appointed to the Wisconsin Conservation Commission on June 17, 1943, just in time to promulgate a new policy designed to alleviate the intense overbrowsing of woodlands that Wisconsin suffered due to its vastly excessive deer herd. As a member of the Citizen's Deer Committee, he had made several recommendations to the Conservation Commission the previous May. He suggested the Commission authorize an antlerless season in the fall, with a complete closure on buck hunting in order to improve the sex ratio of the herd, and concentrate hunting on overbrowsed refuges. Further, he recommended, the Commission should lift the bounty on wolves, and curtail the artificial feeding of deer.

In April, the Leopold family planted 2000 more pines at the shack. They also saw the first natural pine reproduction on the property, probably the result of a fire the previous year.

Earlier that spring the Citizen's Deer Committee inspected deer ranges in northern Wisconsin, where they found record numbers of starving deer, including one hundred fawns. There were apparently no predators of any kind to cull the herd, and there was obvious evidence of severe overbrowsing in the deer range. Leopold had been appointed chairman of the Committee in September of 1942 to conduct an independent evaluation of the deer situation in Wisconsin, especially in the north where deer were threatening to overpopulate their range.

April of 1942 saw four members of the Leopold family, Aldo and Estella, their youngest son Carl, and Estella Jr., plant 1700 pines, junipers, and cedars at the shack.

As chairman of the American Wildlife Institute's Technical Committee, Leopold toured Colorado, Utah, Arizona, Nevada, California, and Oregon in July of 1941. There he saw firsthand the deterioration of deer range throughout the West caused by policies intended to build up the deer herd, including elimination of predators such as mountain lions and coyotes.

Spring planting at the shack that year included 1700 white, jack, and red pines, along with numerous pasque flowers, Dutchman's breeches, and blue phlox.

In March of 1941, Leopold, his mind heavy with news of Hitler's campaign of domination in Europe, diverted with a lecture on War Ecology to his Wildlife Ecology 118 class. He explained the give and take of man's place in the environment, saying, "Nations fight over who shall take charge of increasing the take and to whom the better life shall accrue. Even in peace-time the energies of mankind are directed not toward creating the better life, but toward dividing the materials supposedly necessary for it."

Leopold began to record the number of geese sighted at the shack in April of 1940, and recorded as well the planting of 1500 more pines.

Half of the previous spring's planting of 2300 pines were lost to drought, in spite of Leopold's new desodding procedure around each tree. A handful of bur oak acorns were planted the previous fall to mark a visit to the shack by Charles Elton, an early ecologist whom Leopold admired greatly, and his wife.

That summer, Leopold had been employed by the Huron Mountain Club as a wildlife consultant. He recommended a management plan that included holding the interior of the Club's 15,000-acre tract of virgin hardwood forest near Lake Superior free from logging, so to be preserved as a natural area. He recommended the interior be surrounded by selective logging that would ease deer pressure from without, disperse the deer population within the tract, and encourage songbirds and wildflowers. He also recommended that the Club cease the killing of predators, especially wolves, and allow scientific studies on the land.

As Chairman of the Technical Committee of the American Wildlife Institute, Leopold helped to establish a waterfowl research station, known as the Delta Duck Station, on Lake Manitoba, near Winnipeg, in June of 1938. He installed one of his students, Albert Hochbaum, to work on it. Here, Hochbaum would conduct the research that led to his own stature as preeminent scientist and ecologist. His findings, compiled in the classic Canvasback on a Prairie Marsh, would win him the Brewster Medal of the American Ornithologists' Union and the 1944 Literary Award of the Wildlife Society.

The previous April saw the planting of 100 aspens, hazels, dogwoods, and sumacs, 100 white pines, 500 red pines, 500 jack pines, 500 red oaks, 50 tamaracks, 50 red cedars, 12 wahoo bushes, 40 red osier dogwoods, 30 more hazels, 24 paper birch, and 12 hard maples. This time the family added extra mulch and potash fertilizer to encourage the young plants.

Leopold admitted Albert Hochbaum to the Department of Wildlife Management graduate program in the fall of 1937. Hochbaum had been working with the National Park Service, but intended to pursue his interest in hole-nesting birds. He came to the program equipped with the talent to pursue his goal, a keen mind, and skill in nature drawing.

The previous year's planting of over three thousand cedars, junipers, crabapples, witch-hazel, raspberries, mountain ash, red pine, white pine, and jack pine, suffered great losses to drought and dust storms, leading the family to plant another three thousand pines in the fall.

In the spring of 1936, the Leopold family, that is, Aldo and sons Starker and Luna, had determined to create "a little forest for ourselves" at the shack. The whole family, including Estella, Nina, Carl, and Estella Jr., undertook to plant 2000 pine trees and dozens of mountain ash, juneberry, nannyberry, cranberry, raspberry, and plum. Only a few of the trees survived the nation's raging Dust Bowl that year.

In January of 1935, the Leopold family bought an abandoned farm on the Wisconsin River in Sauk County, along with eighty acres of surrounding land that would be augmented by another 40 acres in later years. The farm included a chicken coop, which the family transformed into a vacation cabin. Leopold started a new journal that day, a journal in which he would record field observations on the property.

He accepted an invitation in October of 1934 to help organize a new "Wilderness Society" through which he was able to promote on-the-ground efforts to preserve American wilderness. The organization was radical, small, and tight-knit.

On June 17, 1934, Leopold and a group of Madison civic leaders and University officials broke ground on the University of Wisconsin Arboretum and Wild Life Refuge. "Our idea," he said, "is to reconstruct [...] a sample of original Wisconsin."

The University of Wisconsin offered a course called Game Management 118 for the first time in March of 1934. The instructor was Aldo Leopold.

Leopold served on the President's Committee on Wild Life Restoration for the Roosevelt Administration beginning in January 1934. The Committee was authorized to develop a national wildlife conservation plan for purchasing submarginal agricultural lands. It included popular cartoonist Jay "Ding" Darling, soon to be head of the Biological Survey.

In October of 1933, Leopold created a wildlife management plan for 500 acres at the University of Wisconsin. This, just after the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation had appointed him to a new chair of conservation with the title Professor of Game Management. The position required teaching a course on game management and overseeing the University's proposed Arboretum. His new five-year contract paid $8000 a year, and brought to an end the hardest times of the Depression for the Leopold family.

For two years, Leopold had been using letterhead that proclaimed him a "Consulting Forester," but there was not much consulting work to be had during the financial depths of 1932-1933. The Leopold family had just been through several months in which they received no income whatsoever.

Leopold attended the Matamek Conference in Quebec in July 1931, an international conference of biologists to discuss cyclic phenomena in nature. He first met Charles Elton there, a Professor of Zoology at Oxford University and author of Animal Ecology, a book that led the way in the modern approach to ecology.

That same summer, Leopold organized and consulted with a group of farmers, calling themselves the Riley Game Cooperative, near Riley, Wisconsin, to implement provisions of the American Game Policy on private lands, including restocking and winter feeding of game. The Cooperative soon became one of Leopold's preferred hunting grounds.

Formulation of the American Game Policy had culminated in December of 1930. Leopold chaired the committee that drafted the final policy, in which the American Game Protective Association called for a national commitment to game management. This was meant to include provisions for regulating take, providing cover and food, and controlling predators. It fundamentally placed responsibility for carrying out these provisions in the hands of landholders, especially the nation's farmers.

Leopold left the United States Forest Service on June 26, 1928, at age 41, to conduct a game survey of north-central states for the Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers' Institute (SAAMI). In the course of his research, he identified two trends: an increase in human population, including hunters, and a decrease in the ability of land to produce game.

Estella Jr., fifth child and second daughter of Aldo and Estella Leopold, was born in 1927.

The family took up archery and bowhunting in 1926, making their own bows out of stocks of osage orange, yew, Port Orford cedar, and Sitka spruce — access to specialty woods being a perquisite enjoyed by the Assistant Director of the USFS Forest Products Laboratory. He had been appointed to the position on July 1, 1924, which required moving the family to Madison from their home in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

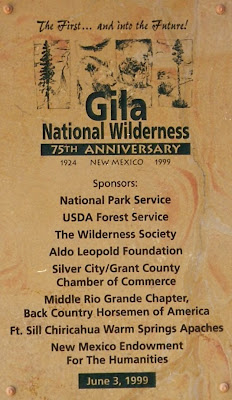

In the month prior, the Gila Wilderness Area on the Apache National Forest of New Mexico was established. It was the first designated wilderness area in the National Forest System. Wilderness was now rare in the Southwest, and Aldo Leopold had been instrumental in planting the seed of desire for designated wilderness areas.

Aldo "Carl" Leopold, fourth child and third son, was born December 18, 1919.

The senior Leopold met with Arthur Carhart that same month to discuss the radical notion of designating forest lands as "wilderness." This was just months after he had rejoined the USFS as Assistant District Forester in Charge of Operations to conduct inspections of National Forests in District 3, report findings, and recommend changes. He had left the Forest Service to work briefly as Secretary for the Albuquerque Chamber of Commerce, where he developed and honed his public relations and organizational skills.

Adelina "Nina" Leopold was born in August of 1917.

Leopold visited the Grand Canyon for the first time in May of 1917, and was disappointed by the "improvements" installed on the rim in order to attract tourists. He had been sent there by the Forest Service to work on a recreational development plan with Frank A. Waugh. Waugh was a leading landscape specialist, dead set against turning the Canyon over to the National Park Service, with its impossibly paradoxical mission to "conserve the scenery [...] and to provide for the enjoyment of the same." Waugh failed.

Leopold spent the fall of 1916 working on the Grand Canyon Working Plan to correct discord between the natural beauty that draws tourists to the Canyon and the impact those same tourists have on the Canyon once they get there.

He was also working with the New Mexico Game Protective Association to enforce newly promulgated hunting laws, establish game refuges on the national forests of New Mexico, and wage war on predatory animals. Leopold had been instrumental in organizing sportsmen (hunters) into Game Protection Associations of Arizona and New Mexico with the goal of increasing game in the southwest.

Luna Bergere Leopold, second son, was born on September 8, 1915.

Leopold was detailed to the USFS Office of Grazing for nine months, where he learned to appreciate "carrying capacity" as applied to stock on forest lands. The Leopold family had moved to Albuquerque, New Mexico in October of 1914 for the new detail.

Aldo Starker Leopold, Aldo and Estella's first child, was born October 22, 1913. The couple had been married on October 9, 1912, at the Cathedral of Saint Francis in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

During the spring of 1912, Leopold planned and built the supervisor's quarters on the Carson National Forest at Tres Piedras, New Mexico. He built the small but elegant house around a great fireplace, facing the Sangre de Cristos mountains to the east, for $650. The new home was necessary because Leopold had fallen in love with Estella Bergere, the daughter of a prominent Santa Fe family that could trace its roots back to captains of Cortez and Coronado. The State of New Mexico was admitted to the Union in January of that year, largely due to the efforts of Estella's uncle, Solomon Luna.

Leopold was promoted to Supervisor of the Carson National Forest in northern New Mexico in May of 1911. He had previously been assigned as Crew Chief of a reconnaissance party to survey the Blue Range on Apache National Forest in Arizona and New Mexico. This assignment was a disaster for the young forester: He made crucial mathematical errors to the baseline survey, which threw the rest of the survey off, and made enemies of everyone on his crew. In spite of this, his superiors in the Forest Service felt he showed a good deal of promise.

He climbed Escudilla Mountain upon arrival in Springerville, Arizona, in July of 1909, having reported to work for the US Forest Service on the 3rd of that month. He had just completed 10 weeks of Forest Service training in New Orleans, after graduating from Yale University with a Master of Forestry degree. The Class of '09 included 35 foresters dedicated to the ideas and ideals of Gifford Pinchot, benefactor to the Yale Forest School, father of utilitarian forest management, and first Chief of the United States Forest Service.

Before Yale, Leopold attended the Lawrenceville School for two years of college preparation, having attended public schools in Burlington, Iowa until that time. He was known among his schoolmates and the community as a local expert in matters of ornithology, having developed his interest in birds and natural history while growing up in a mansion overlooking the Mississippi River, atop Prospect Hill in Burlington.

He was born Rand Aldo Leopold on January 11, 1887 to Carl Leopold and Clara Starker Leopold, first cousins and descendants of displaced aristocracy cum frontier nobility. From his father, young Aldo learned the ways of Nature, including a deep respect for life that was exhibited in Carl's self-imposed bag limits and hunting rules to encourage the local populations of waterfowl at a time when the migrating flocks were obviously declining. He also took from his father the drive to do things right: Carl ran the family business — the Leopold Desk Company — with the motto, Built on Honor to Endure. From his mother, he learned to love literature, philosophy, and poetry, especially that of Henry David Thoreau and Jack London.

At age eleven, Leopold wrote in his composition book that he liked to study birds in general, and wrens the best of all, "because they do more good than almost any other bird." He began keeping an ornithological journal in 1902, a habit he would retain for life.

When Aldo left for Lawrenceville, his mother's first letter, sent while his train was still steaming eastbound, pleaded with her son to give "his last thought at night to his mother." His father implored him to "write us fully, my boy, as often as you can every detail of your life in school as it will be of interest to us." And he did.

At the Lawrenceville School, he wrote home every day, often describing his tramps through nearby woods and his latest nature sightings. As an adolescent his phrase was often flowery but prophetic, once writing: "We can put on paper that such-and-such flowers are added to the list, that these birds have arrived and those are nesting, but who can write the great things, the deep changes, the wonderful nameless things, which are the real object of study of any kind."

As a young Assistant Director on the Carson National Forest, in June of 1911, Leopold started a newsletter called The Pine Cone "to scatter seeds of knowledge, encouragement, and enthusiasm among the members and create interest in the work. May these seeds fall on fertile soil and each and every one of them germinate, grow, and flourish...." Leopold served as chief editor, reporter, and illustrator.

While working to organize sportsmen in Arizona and New Mexico, he published another paper called The Pine Cone for that audience. This second newsletter was meant "to promote the protection and enjoyment of wild things. As the cone scatters the seeds of the pine and fir tree, so may it scatter the seeds of wisdom and understanding among men, to the end that every citizen may learn to hold the lives of harmless wild creatures as a public trust for human good." Early issues called for "the reduction of predatory animals ... the wolves, lions, coyotes, bob-cats, foxes, skunks, and other varmints," and hailed the killing of an infamous grizzly bear, saying, "the king of Mt. Taylor was a cow-killer from away back. He was a bad egg. He ate a thousand dollars' worth of beef a year. The destructiveness of cow-killers is intolerable, and it is highly desirable that they be destroyed on sight."

During this time he began keeping a hunting journal. His first entry recorded the day's take of three doves on the Rio Grande flats, along with some self-criticism. "Shot poorly," he wrote.

He began publishing articles in journals and periodicals in 1918, including an article in Outers Book — Recreation called "The Popular Wilderness Fallacy." In another article called "Forestry and Game Conservation," Leopold first compared game management to forest management, saying, "Forestry may prescribe for a certain area either a mixed stand or a pure one. But game management should always prescribe a mixed stand — that is, the perpetuation of every indigenous species. Variety in game is quite as valuable as quantity." Though aware of the need for biodiversity, his awareness at this point did not yet include a need for predators, even in wilderness.

He addressed a group of University of Mexico students in October of 1920. In speaking to them on "A Man's Leisure Time," Leopold declared that he spent his own leisure "entirely in search of adventure, without regard to prudence, profit, self-improvement, learning, or any other serious thing." He applauded others who spent their leisure time working to educate themselves in natural history and recommended such pursuits to his audience.

Another article in a 1921 edition of the Journal of Forestry titled "The Wilderness and Its Place in Forest Recreation Policy" was the profession's first treatment of wilderness. The seasoned forester wanted "to give definite form to the issue of wilderness conservation, and to suggest certain policies for meeting it, especially as applied to the Southwest." Furthermore the article asked "whether the principle of highest use does not itself demand that representative portions of some forests be preserved as wilderness." It recommended setting aside the headwaters of the Gila River in the Mogollon Mountains of New Mexico as a prototype wilderness area.

From 1924 to 1928, Leopold worked on a book he wanted to write called Southwestern Game Fields, but never completed for several reasons. He was experiencing difficulty communicating with his primary contributors in the field, when at the same time they began reporting of a disaster on the Kaibab National Forest. The forest had been swept clean of predators and the deer were now overbrowsing the range to the point of their own starvation. This new data required Leopold to completely rethink his stance on predator control. During this period, he also wrote numerous articles on game management, technical forestry, and wilderness.

He spent the better part of 1930 writing Report on a Game Survey of the North Central States, based on the SAAMI Game Survey, and immediately formulated plans to write an accompanying book. This now-classic textbook on game management would be more encompassing than Southwestern Game Fields, using the latest in field research, and based on a series of lectures Leopold had presented at the University of Wisconsin.

He devoted the first six months of 1931 to writing Game Management, while the nation and the Leopold family languished in the grasp of the Great Depression. Charles Scribner's Sons agreed to publish Game Management if Leopold would agree to certain reductions in production costs and contribute $500 of his own money. Leopold agreed, and signed a contract with Scribner's on January 11, 1932 — Leopold's 45th birthday. He worked diligently on Game Management throughout 1932, and sent the final manuscript to Scribner's on July 16, 1933.

In October of 1933, Leopold wrote "The Conservation Ethic" for the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Here Leopold showed the direction in which he was heading after writing Game Management, saying the goal of conservation "is a universal symbiosis with land, economic and esthetic, public and private."

Critical acclaim and material reward soon began to accrue from the publication of Game Management, By November of 1933, 1900 copies had been sold and the book soon became a required text for students of wildlife conservation in America. That same month, Leopold received his first royalty check of $675 — not a bad sum for Depression times.

In 1935, Leopold first used the phrase "land ethic" in an address called "Land Pathology" given at the University of Wisconsin. While the country choked on the product of its own abuse of the land during the Dust Bowl, Leopold said, "Philosophers have long since claimed that society is an organism, but with few exceptions they have failed to understand that the organism includes the land which is its medium[.]" Further, forces required to stabilize the land could "eventually yield a land ethic more potent than the [forces themselves], but the breeding of ethics is as yet beyond our powers."

Leopold published "Marshland Elegy" in the October issue of American Forests to celebrate the sandhill crane and lament its loss in Wisconsin's marshlands. He later delivered "Natural History, the Forgotten Science" at the University of Missouri, in which he criticized the natural history curriculum. He also wrote more than thirty popular articles for the Wisconsin Agriculturalist and Farmer in order to provide the farmer with basic information needed to practice wildlife conservation on the farm. It was at this time that Leopold first used the word "ecology," and delivered an address on "A Biotic View of Land" to a joint meeting of the Society of American Foresters and the Ecological Society of America, in which he discussed the relationship between ecology and conservation.

By the end of 1941, Leopold was seriously considering writing an illustrated series of ecological essays. He discussed the idea with Harold Strauss, an editor at Knopf, but his busy schedule kept getting in the way. He began writing in earnest in late 1943, beginning with one of his personal favorites, "Great Possessions" in September, followed by "Illinois Bus

Ride" on New Year's Day, 1944, and "The Delta Colorado" several days later. He wrote "Thinking Like a Mountain" on April 1, 1944 in response to Albert Hochbaum's proddings to admit his own guilty role in the extermination of predators in the Southwest. Leopold and Hochbaum had discussed the idea of Hochbaum illustrating Leopold's essays, but constraints on Hochbaum's time prevented collaborating with the former student while he researched and wrote Canvasback on a Prairie Marsh.

Leopold delivered an address to the Conservation Committee of the Garden Club of

America in June 1947 on "The Ecological Conscience," "an affair of the mind as well as the heart. It implies a capacity to study and learn, as well as to emote about the problems of conservation."

He wrote "The Land Ethic" in the summer of 1947 to summarize his ecological essays. His capstone piece was created largely by combining and rewriting "The Conservation Ethic," "A Biotic View of Land," and "The Ecological Conscience" from earlier publications and addresses.

Leopold met with Charles Schwartz to discuss illustration of the book in the summer of 1947. Schwartz was an illustrator then working with the Missouri Conservation Commission who had been introduced to Leopold by his son, Luna.

He sent a manuscript to Knopf in September 1947, but editor Clinton Simpson promptly

rejected the book, saying "What we like best is the nature observations, and the more objective narratives and essays. We like less the subjective parts — that is, the philosophical reflections[.] In short, the book seems unlikely to win approval from readers or to be a successful publication as it now stands."

Disappointed but undaunted, Leopold wrote "Axe-in-Hand" in November of 1947, and a new, more concise, foreword in December. Meanwhile, his, son, Luna, felt Leopold was not given fair treatment by Knopf and began negotiations with Oxford University Press and William Sloane Associates of New York.

Leopold wrote "Good Oak" in early 1948, and on the same day that he voted against hydroelectric dams in Wisconsin, he wrote to Carl Russell, superintendent of Yosemite National Park, to oppose construction of a highway through Tioga Pass, saying, "I think the Park Service has already acquiesced in far too much motorization, and that the time to call a halt on that process is now, while there are still some wilderness values left to conserve."

He continued to edit the manuscript and, on Wednesday, April 14, 1948, Phillip Vaudrin, editor at Oxford, called Leopold to say Oxford would like to publish the book. Leopold wired Charlie Schwartz with the good news on Thursday, April 15, then wrote to Luna to thank him for his efforts in getting the book published.

On Wednesday, April 21, Leopold recorded sighting 871 geese at the shack, the most geese he had ever recorded in all of his journals.

About 10:30 that morning, smoke was spotted on a neighbor's farm...

SOURCES

- Coggins, G. C., et al. 1993. Federal Public Land and Resources Law

- Meine, C. 1988. Aldo Leopold: His Life and Work

No comments:

Post a Comment